Swap Logic: Making One Function Do Many Things in Rust

When you’re writing Rust functions, it’s tempting to bake specific behaviour directly into the implementation. But what happens when requirements change? You end up with duplicate functions or sprawling conditional logic. There’s a better way: separate the mechanism from the policy.

The Problem: Hardcoded Behaviour

Consider a simple event processor that extracts payloads from a list of events:

struct Event {

kind: String,

payload: i32,

}

fn process_events(events: Vec<Event>) -> Vec<i32> {

events.iter().map(|e| e.payload).collect()

}

This works fine—until you need to double the payload values. Or extract the length of each event’s kind string. Suddenly, you’re either duplicating process_events with slight variations or adding parameters and conditionals that make the function increasingly brittle.

The Solution: Inject the Behaviour

Instead of hardcoding what to do with each event, pass that logic in as a parameter. Rust’s closures make this elegant:

fn process_events<F>(events: Vec<Event>, handler: F) -> Vec<i32>

where

F: Fn(&Event) -> i32,

{

events.iter().map(|e| handler(e)).collect()

}

// Now the caller decides:

process_events(events.clone(), |e| e.payload); // extract payload

process_events(events.clone(), |e| e.payload * 2); // double it

process_events(events, |e| e.kind.len() as i32); // measure kind

The function now handles only the mechanics—iteration and collection. The actual transformation logic lives in the caller-provided closure. This is the essence of mechanism/policy separation: the library provides the plumbing, the user provides the logic.

Why This Matters

This pattern isn’t just about avoiding duplication. It’s fundamental to library design in Rust:

Flexibility: One function adapts to countless use cases without modification. Need to filter events first? Add logging? Access external state? Just change the closure.

Testability: You can test the mechanism independently from specific behaviors. Mock handlers become trivial to write.

Composability: Higher-order functions like this compose beautifully. Chain them together, wrap them in error handling, or integrate them into larger systems without touching the core logic.

You’ll see this pattern throughout the Rust ecosystem. Web frameworks like Actix use it for request handlers. Iterator adapters like map and filter are built on it. Even async runtimes rely on user-provided futures to determine what work gets done.

From Rigid to Reusable

The shift from hardcoded behaviour to pluggable handlers is more than a refactoring technique—it’s a mindset. When you design functions that accept closures, you’re building APIs that grow with your users’ needs. Your code becomes a toolkit rather than a script, capable of solving problems you never anticipated.

Next time you write a function, ask yourself: am I hardcoding policy that could be injected? That small change often makes the difference between throwaway code and a reusable library component. In Rust, with zero-cost abstractions and powerful type inference, there’s no reason not to design for flexibility from the start.

Simplified version?

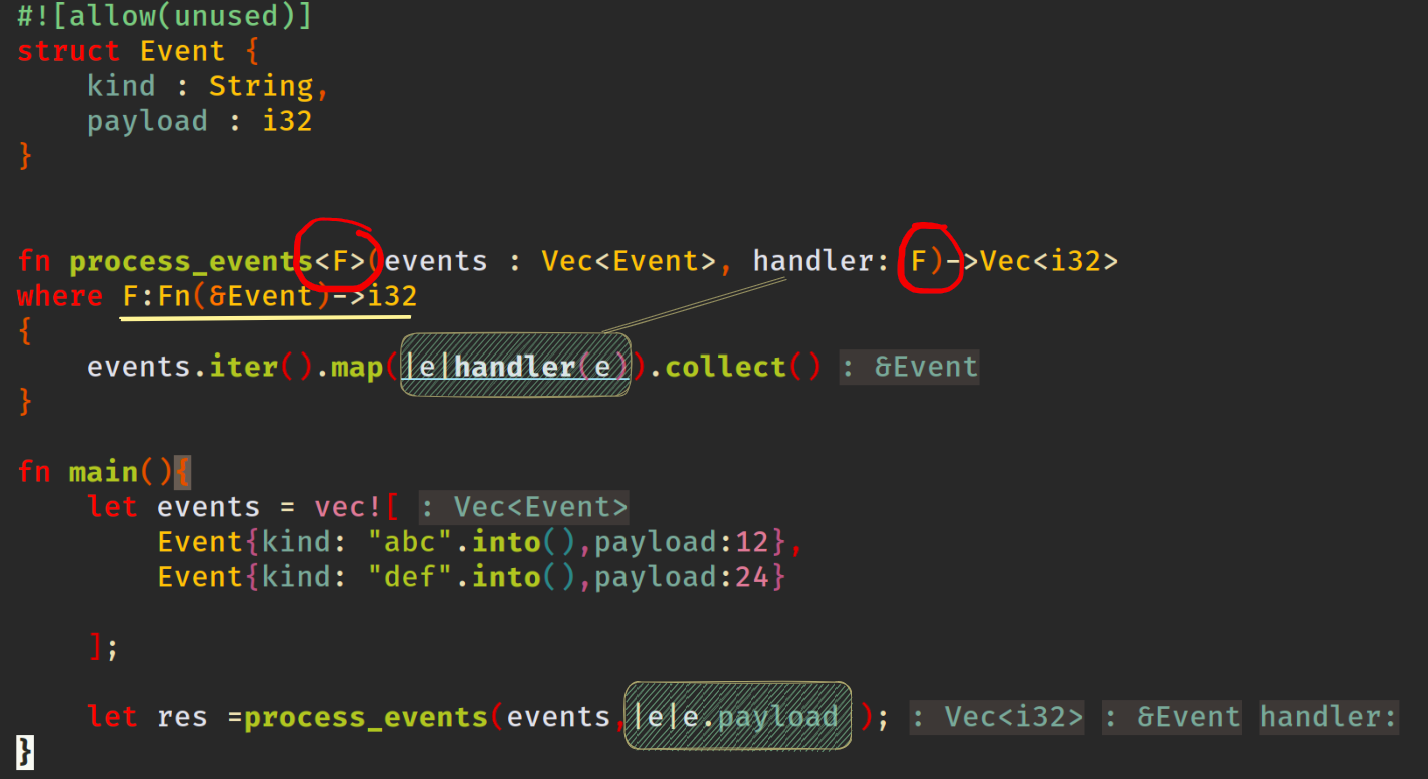

This is Rust code demonstrating higher-order functions and closures.

The Event Struct

struct Event {

kind: String,

payload: i32

}

A simple data structure holding a string kind and an integer payload.

The process_events Function

fn process_events<F>(events: Vec<Event>, handler: F) -> Vec<i32>

where F: Fn(&Event) -> i32

This is a generic function that:

- Takes a vector of

Eventobjects - Takes a function

handler(typeF) that accepts an&Eventreference and returns ani32 - The

whereclause constrainsFto be any function matching that signature - Returns a vector of

i32values

The function body processes events by iterating through them, applying the handler to each event, and collecting the results into a new vector.

The main Function

Creates two events and then calls process_events with a closure:

|e| e.payload

This closure takes each event e and extracts its payload field. The circled annotations show:

- The generic type

Fgets filled in with this closure type - The closure is passed as the

handlerparameter - It extracts the

payloadfrom each event

So res ends up being vec![12, 24] – just the payload values from both events.

This pattern is common in Rust for creating flexible, reusable functions that can work with different processing logic supplied by the caller.