Handler Pattern in Rust: Closures Inside Process Functions

Handlers #2

If you have ever looked at the code for a Rust web framework like Axum or Actix Web, you’ve seen the “Handler Pattern” in action. You define a function that does specific business logic, and somehow the framework knows exactly when to call it and what data to feed it.

Often, this seems like magic. But under the hood, it’s usually just a powerful application of Rust closures and generics.

In this article, we will de-mystify the pattern of passing a “handler closure” into a “process function.” We will move beyond the basics and look at a real-world scenario where the process function manages the workflow and the handler manages type conversion.

The “Why”: Separation of Concerns

Why do we complicate things by passing functions into other functions?

Imagine you are building a system that downloads files. The steps are always the same:

- Connect to the URL.

- Download the bytes.

- [DO SOMETHING WITH THE BYTES].

- Close the connection and log the result.

Steps 1, 2, and 4 are “boilerplate.” They never change. Step 3 is the only variable. Sometimes you save the bytes to disk, sometimes you parse them as JSON, sometimes you unzip them.

Instead of writing three different functions that copy-paste steps 1, 2, and 4, you write one “Process Function” that handles the workflow, and you pass in a “Handler Closure” that defines the variable action.

This is Inversion of Control. The process function doesn’t know what you want to do with the data; it only knows when the data is ready for you.

The Core Components

To make this work in Rust, we need two things acting in concert:

- Generics: To allow our process function to accept any valid closure.

- Trait Bounds (

Fn,FnMut,FnOnce): To tell the compiler exactly what the closure is allowed to do with its environment.

Here is the simplest possible skeleton:

Rust

// The "Process Function" holds the workflow.

// <F> is a generic type parameter.

fn run_workflow<F>(handler: F)

// The "where" clause defines the rules for F.

// Here, F must be a closure that takes no arguments and returns nothing.

where

F: Fn(),

{

println!("1. Workflow started.");

// Call the handler at the right time

handler();

println!("3. Workflow finished.");

}

fn main() {

// We pass a closure into the function.

run_workflow(|| {

println!("2. The handler is running its custom logic!");

});

}

The Challenge: Different Return Types

The basic example above is neat, but real-world Rust is rarely that simple.

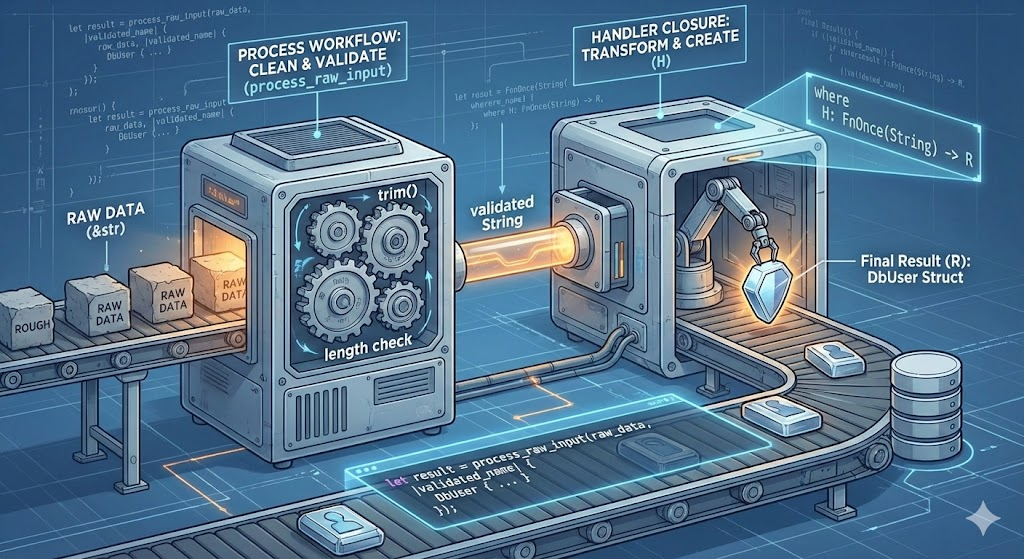

A very common requirement is a “pipeline” scenario. The process function takes raw input, performs initial cleaning or validation, and then hands that clean data to the handler. The handler then transforms that data into a final, completely different type.

Let’s build an example.

The Goal: We need a system that processes incoming raw usernames.

- The Process Function: Takes a messy raw string slice (

&str). It trims whitespace and validates length. - The Handler: Takes the validated string and converts it into a structured

DbUserobject.

To achieve this, our process function needs two generic parameters: one for the handler itself (H), and one for the handler’s return type (R).

The Complete Example

// This is the final structure we want to end up with.

#[derive(Debug)]

struct DbUser {

username: String,

active: bool,

}

// --- THE PROCESS FUNCTION ---

/// This function handles the workflow of validating raw input.

/// It doesn't know what the final output format will be; it delegates that to the handler.

///

/// H: The type of the handler closure itself.

/// R: The specific type that the handler will return.

fn process_raw_input<H, R>(raw_input: &str, handler: H) -> Result<R, &'static str>

where

// The handler must take an owned String and return type R.

// We use FnOnce because we are handing ownership of the string to the closure

// and we only need to call it one time.

H: FnOnce(String) -> R,

{

println!("PROCESS: Starting validation workflow on '{}'...", raw_input);

let trimmed = raw_input.trim();

if trimmed.is_empty() {

return Err("Input cannot be empty");

}

if trimmed.len() < 3 {

println!("PROCESS: Validation failed.");

return Err("Username too short");

}

println!("PROCESS: Validation successful. handing off to handler.");

// --- HANDLER CALL ---

// The workflow is complete. We hand ownership of the cleaned

// data to the closure and return whatever the closure produced.

let final_result = handler(trimmed.to_string());

Ok(final_result)

}

// --- USAGE ---

fn main() {

let raw_data = " rusty_user_99 ";

// We call the process function.

// Notice how the closure takes a String, but returns a DbUser struct.

let result = process_raw_input(raw_data, |validated_name| {

println!("HANDLER: Received validated name: {}", validated_name);

// The handler's job is purely transformation

DbUser {

username: validated_name,

active: true,

}

});

match result {

Ok(user) => println!("SUCCESS: Created database entry: {:?}", user),

Err(e) => println!("ERROR: {}", e),

}

println!("\n--- Running a failing example ---");

let _ = process_raw_input("yo", |_| {

// This closure won't even run because validation fails first

println!("This will not print");

});

}

Why this works

Let’s look closely at the signature of the process function:

fn process_raw_input<H, R>(raw_input: &str, handler: H) -> Result<R, &'static str>

- We accept an input argument

&str. - We accept a handler generic

H. - We declare that this whole function will eventually return an

Okcontaining typeR(or an error string).

Now look at the where clause:

where H: FnOnce(String) -> R,

This is the contract. We promise the compiler that whatever closure we pass in for H, it will accept one String argument, and it must return type R.

Because R is generic, the compiler figures out what it is based on the closure we actually write in main(). Since our closure in main returns a DbUser struct, the compiler determines that R becomes DbUser for that specific call.

Summary

Using closures as handlers inside process functions is a fundamental pattern in idiomatic Rust.

It allows you to maintain clean separation between “infrastructure code” (the process function’s workflow, validation, and error checking) and “business logic” (what the handler does with the resulting data). By mastering generic types for both the handler function and its return type, you gain the flexibility to build highly reusable and testable systems.

“Use the generic handler pattern when you need reusable validation for multiple output types. Otherwise, a simple function is clearer and more maintainable. Don’t reach for generics just because they’re cool—use them when they solve a real problem.”